How queer it is to be moved by a room. It happened to me in Sils-Maria, a place I now carry with me. I stood on the doorsill of the cordoned-off restricted space where a man of great intellect had sat at a small desk – the original piece of furniture still there – and pondered the human condition by lamp light. He had rented this room in a private boarding house in a remote village in the Swiss alps, hoping the mountains with their pure glacier air would act as a restorative. I imagined him breathing in deeply as he opened the small window, letting his gaze rest on the stoic grandeur of the scenery, contemplating the path of his first walk when daylight faded.

Some of his copious notes and manuscripts were displayed downstairs: his philosophical stance was controversial − God is dead. For a long time his name evoked the excesses of fascism and Nazism but dedicated scholars continued to engage with his work as philosopher, cultural critic, Latin and Greek scholar, and artist. Today German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche is generally viewed as having exerted a profound influence on Western culture and modern intellectualism.

That holiday room, where he spent so many hours ruminating and writing, making palpable ink marks on paper as he held poor health and incipient madness at bay, moved me. Not as a student of philosophy or as an admirer of his intellectual prowess but as a writer. It frightened me to know that at the age of 44 he succumbed to mental illness, . His modest upstairs room came last in the museum tour. You came to it after studying the well-lit writings and photographs and mementoes, on walls and in display cabinets, of other great thinkers and writers whose lives had intersected with his. The Jewish doctor and scholar who believed Nietzsche’s ideas had been misappropriated and devoted his writing to bringing the philosopher’s legacy to public attention. The Italian Swiss poet Remo Fasani who wrote exquisite lines in Italian that pre-empted any attempt of mine to distil that room and its emanation into something true.

We’d come to visit Sils-Maria after I’d overheard snatches of a conversation between a German lawyer who knew the area well and a Canadian girl in my ski school group. Sils-Maria. You cannot come to St Moritz and not go to Sils-Maria. My skin had prickled at the older woman’s hushed tone; she spoke as people do when a place is special, its effect not quite explainable, as when one has had some kind of a spiritual awakening.

And she was not wrong. It cast a spell over us, its visitors, from the moment we left our car on the outskirts and wandered into the radius of its strange magnetism. It was an entrancing place in the frosty light of late afternoon with its majestic mountains, in the distance a flat plain with solitary trees on the edge of a lake, the wintry sun an incandescent fireball trailing pale golden light across the horizon and onto the shimmering surface as walkers roamed its shores. We walked into the picturesque village and peered into garlanded shop windows, the dream landscape enveloping us, feeling as if we’d stepped into a Christmas snow globe. A local pointed us in the direction of the best bakery and coffee shop in town.

The woman behind the coffee shop counter considered my question, eyed the soft toy husky puppy in my hands, thought a little, tried a name out as she looked at it, shook her head, and then said in decent English, “Olaf. Yes, Olaf. Maybe that is a good name?” I tried it out, holding the furry toy in my hand and looking into its arctic blue baby dog eyes. I’d expected Swiss but I’d gotten Russian. Olaf. It was perfect. I explained it was a gift for my nephew in South Africa. She smiled, popped it into a bag, and processed my credit card. The coffee and cake was excellent.

That’s the kind of town it was. It made you feel as if you’d stepped into a magical fault line where a perfect place existed, but the moment you drove away, or acted outside of some unwritten set of laws regarding what it meant to be a civilised human, then it would no longer exist. Then all that remained would be a thick white fog where ghosts roamed unhampered by visitors, and you’d never find it again.

Refreshed, we donned thick jackets once again and headed for the impassable striated mountains just beyond the town, under a traffic boom, past converted luxury apartment blocks in the shadow of the town’s only ski lift, past traditional homes with curious paintings on their walls and grand old-time hotels, past an avant-garde glass barn house on a flat open field its relaxed occupants clearly visible, past the town library with its carved wooden totems.

The soft falling snow grew denser. Horse carriages with passengers passed us in the gloam, the clip-clop of trotting hooves echoing eerily as they disappeared into whiteness. Realising we’d lost track of time we hurried back to the Nietzsche-Haus museum we’d seen on our way in. As we approached the tall narrow house, dusk settling around us in descending ruffles of pluming darkness, we saw lamps had been lit in some rooms and ceiling lights illuminated others. It was set a little back from the road with a long straight path and stairs that went up to an entrance porch. The front door opened as we reached it and a young Japanese couple slipped out as we slipped in.

Portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche by Edvard Munch, 1906

P.S. It is widely believed that Nietzsche’s final descent into the darkness of dementia was triggered by an act of cruelty to an animal. In 1889 Nietzsche witnessed a horse being whipped within an inch of its life by a coach driver in Turin. He rushed to the horse’s aid, embracing it and refusing to let go, and the police had to be called. I didn’t know about the Turin horse when I stood on the sill of that humble and sombre room, but somehow it seems apt.

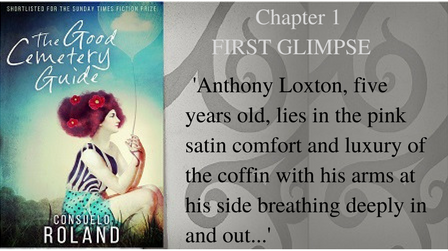

custom-fitted red spotlights on its front bonnet and the clever graphic of part of a guitar superimposed over the outline of a coffin. It had the effect of a pink skeleton casually deposited on the pavement. I thought it was perfectly suited to the quirky eccentricity of Anthony Loxton, third generation funeral director and accoustic guitar muso, but my publisher preferred the arum lily version.

custom-fitted red spotlights on its front bonnet and the clever graphic of part of a guitar superimposed over the outline of a coffin. It had the effect of a pink skeleton casually deposited on the pavement. I thought it was perfectly suited to the quirky eccentricity of Anthony Loxton, third generation funeral director and accoustic guitar muso, but my publisher preferred the arum lily version.

challenge deaf gods, a liking for eccentric headgear. Something subtle and paradoxical has drawn me into her scene as surely as if it were from a famous play with important themes, performed by a world-renowned actor.

challenge deaf gods, a liking for eccentric headgear. Something subtle and paradoxical has drawn me into her scene as surely as if it were from a famous play with important themes, performed by a world-renowned actor.

Soundtrack by R.E.M., The Beatles, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Youssou N’Dour, Bob Marley

Soundtrack by R.E.M., The Beatles, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Youssou N’Dour, Bob Marley

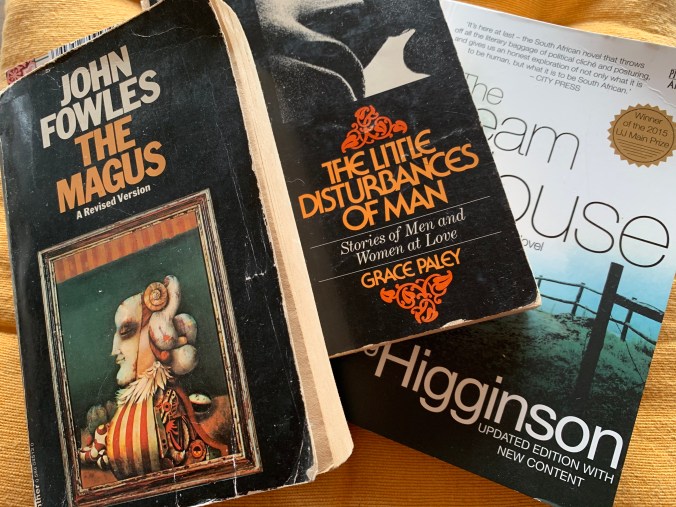

What can I say? I suffer from book cover OCD. It explains everything. The long hours, the diversions, the steep learning curve as I hunted the right image and then the right cover design down…

What can I say? I suffer from book cover OCD. It explains everything. The long hours, the diversions, the steep learning curve as I hunted the right image and then the right cover design down…